Hello World,

Sorry I had to do it. Write in the third person that is. I just couldn’t figure out how to state the fact that I have written my first novel without being a little extra. And referring to yourself in the third person is as extra as you can get on a written page. So pardon me for being braggadocios. It’s just that I’ve written a novel that I’m extremely proud of and it’s finally time to tell you all about it!

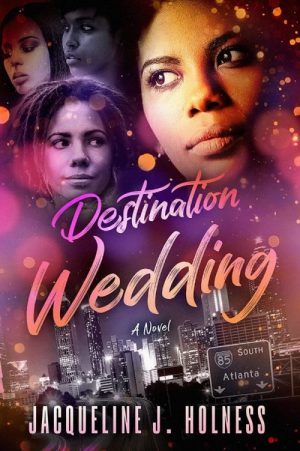

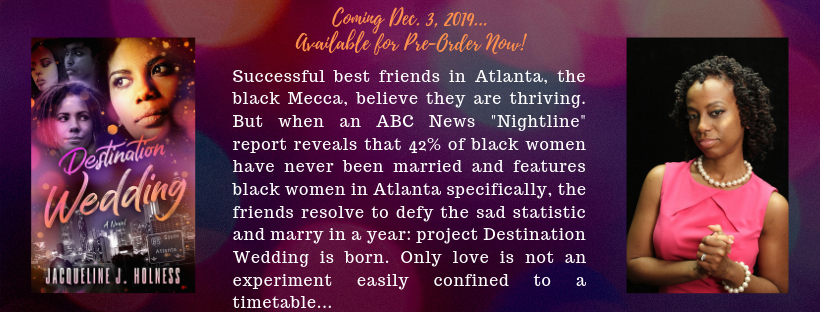

When I first imagined myself as a writer at the adorable age of six, I saw myself weaving words into worlds as a novelist. Well, maybe not a quite a novel, but certainly a work of fiction. As I matured and began to grasp that writing was not as simple as it seemed, I gravitated toward journalism where real life (just the facts, ma’am) was written down and every story was thankfully short. I just didn’t think I had enough words to write a whole novel. But in my heart, behind the wall of fear, I wondered if I would ever summon enough stamina and skill to craft a world of words also known as a novel. In 2009, yes, 10 years ago, a real-life event took hold of me and demanded that I explore this topic as a novel. And it literally took me 10 years to learn how to write a novel AND get it published. So Destination Wedding written by Jacqueline J. Holness (oh so extra I know) will be released in December to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the real-life event that inspired me and captivated me enough to write a novel at long last! So below is the synopsis followed by my interview with 96Kix’s Kimberly Kaye, who interviewed me as I wrote Destination Wedding. (Read and or listen to the interview.)

Three successful best friends in Atlanta believe they are thriving in the Black Mecca. Bossy bank executive Senalda breaks down men from business to bed no holds barred. Hip hop PR guru Jarena praises the Lord and pursues married men with equal persistence. Famous and infamous radio personality Mimi fights with her fans and for the love of her on-and-off-again boyfriend.

But when an ABC News Nightline report, “Single, Black, Female — and Plenty of Company,” asks why can’t a successful black woman find a man? The friends are suddenly hyper-aware of their inclusion in the sad statistic: 42% of black women who have never been married. Like the women in the report, they are career-driven, beautiful black women living in Atlanta who have everything — but a mate. They resolve to defy the statistic by marrying in a year and have it all by tackling their goal as a project with a vision board, monthly meetings, and more. Project Destination Wedding is born. A “happily married” best friend Whitney is a project consultant.

But as the deadline ticks closer, the women wonder if they can withstand another year of looking for love in the media-proclaimed no-man’s land of Atlanta. Senalda wrests a marriage proposal from the male version of herself, but the proposal comes simultaneously with a devastating secret. Jarena unleashes hell when her call to ministry coincides with dating her married college sweetheart. Mimi faces losing her career and jail time chasing her boyfriend and marries another man in the process. Whitney’s power couple profile plummets when her husband, a pornography addict, announces he would rather pursue photography than be an MD.

Inspired by an actual Nightline report, Destination Wedding charts four women’s journeys as they discover that love is not an experiment easily confined to a timetable.

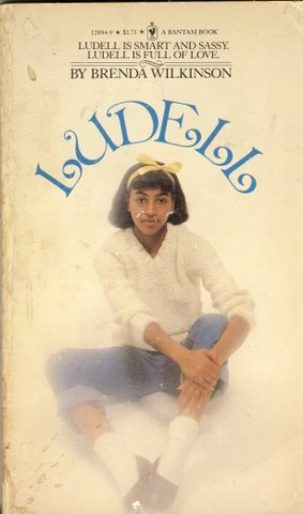

These are the four main characters as I saw them in my mind as I was writing- Jarena, Mimi, Senalda & Whitney…Can you match the women to how they actually turned out on the cover?

Kimberly: 96 KIX. On the line with me, I have Jacqueline Holness. How are you Jacqueline?

Jacqueline: I’m great. How are you Kimberly?

Kimberly: I’m wonderful. Welcome back to the show!

Jacqueline: Thank you so much for having me!

Kimberly: You know the last time you we talked it was all about ‘After the Altar Call.’ Now, what have you been up to? I know I always read your blog. Always.

Jacqueline: Thanks so much for reading. I really appreciate that. You never know who is reading. Thank you so much.

Kimberly: How is it working with the blog?

Jacqueline: Well, I love to write so it’s a creative outlet for me. And I’m always surprised when people actually respond to what I write because it’s not something that I get paid to do. I just love to do it. Even if people didn’t read it, I would still write.

Kimberly: You said, regardless, you’re gonna blog!

Jacqueline: Yes! Definitely.

Kimberly: Now, how do you pick your topics to know what to blog about?

Jacqueline: Well, the most important aspect of my life is my faith so I always want to talk about my faith and whatever area I choose to talk about whether it be pop culture or whether it be more serious issues, I always try to look at it through the lens of having faith in God and how God would want us to see certain things that play out in our society.

Kimberly: Right, well that’s great. Now, also I saw that you are getting ready to write another book for us.

Jacqueline: Yes, I grew up reading fiction books, but when I got older, I just veered off into non-fiction books. But recently, I rediscovered my love of fiction and I decided to write a fiction book about three single black women in Atlanta.

Kimberly: Alright. Can you give us a little bit more? Or is that all you can give us?

Jacqueline: (Laughter) I’ll tell you a little more about it, but I’m not finished yet. But basically, I’m not sure if you saw the ABC News Nightline special that came on in December 2009 where it was quoted that 42% of black women have never been married?

Kimberly: Wow! That’s a high percentage.

Jacqueline: Yes, a very high percentage and they featured black women in Atlanta who had everything but a mate. And from there, there was a debate that was held in Atlanta. Steve Harvey was here. Sherri Shepherd. A lot of notables came in town to debate this issue in Atlanta. So as a black woman, I was single at the time, I’m married now, it really impacted me. And I thought what if I wrote a book about black women, fictional black women, who saw this report, and decided to defy the statistics and get married in a year.

Kimberly: Now you live in Atlanta?

Jacqueline: I do live in Atlanta.

Kimberly: Do you see that problem?

Jacqueline: Well, I see it all over. When I travel, I meet a lot of single black women, but for some reason, Atlanta seems to be the epicenter I guess of single black women. And because I was single and just got married at 40 years old, I know what it’s like to be single and I know what it’s like to wonder, ‘Why aren’t men choosing me?’ So I decided to write a book from my own personal journey and do it through the lens of fiction.

Kimberly: That sounds great. Do you know when you will be finished?

Jacqueline: Well, I hope to have the rough draft finished very soon. I’m going to work on it for the next few months. What interested you when you read, I know you read the blog post about me working on this book. What interested you? I’m just curious.

Kimberly: Like you said, we have a lot in common, Jacqueline. I got married when I was 40. Same thing.

Jacqueline: Oh really?

Kimberly: Yes, we have that in common. I was going through life, and I was like, ‘I don’t think I’m gonna ever get married.’ But once I quit thinking about it, dwelling on it, it happened so that’s what kind of intrigued me. It takes a lot. You wonder, Am I doing something wrong? Is it me? Why didn’t I get married when I was in my 20s or in my 30s? So that’s why I was interested.

Jacqueline: Wow! So I’m so glad we have that in common. We may have to talk off the air later about that as older women who have gotten married. That’s a category in itself – older brides. I may have to write something about that.

Kimberly: (Laughter) Yes! Well, I’m anticipating it.

Jacqueline: Yes, well, please go to my website AftertheAltarCall.com and you will see updates about the book. I’m really excited about, and I hope it will be on bookshelves as soon as possible.

Kimberly: And that’s also why I wanted to talk to you. I wanted to spread the word about your blog. I think it’s just terrific, and I want everyone to be aware of it.

Jacqueline: Oh, thank you so much!

(Note: There is just a minute or so more left of the interview, but I included what pertains to today’s blog post.)

Below are some advance reviews I have received about Destination Wedding!

“Jacqueline J. Holness has penned a delightful read that puts a new spin on the age-old dilemma of the beautiful, successful, single black woman finding a mate! Did I say beautiful and successful? Set in the Black Mecca – The ATL – Destination Wedding will have you asking, “Why is this so hard?” I found myself in the moment, rooting for these women – and thoroughly enjoyed their journeys to happily-ever-after.” – Monica Richardson, author of the Talbots of Harbour Island series

“In need of a getaway? Destination Wedding is the read you need. Filled with characters that will remind you of your girlfriends and unexpected adventures, it’s the perfect vacation read.” – Chandra Sparks Splond, author and blogger

“In Destination Wedding, Jacqueline J. Holness takes readers on page-turning twists and turns that hijack several friendships on the path to love. If you’re eager for an entertaining read that will leave you rooting for the characters as if they’re your friends, pick up your copy today.” – Stacy Hawkins Adams, multi-published author of Coming Home, Watercolored Pearls, The Someday List and more

So Destination Wedding will officially debut on Dec. 3, but it is available for pre-order on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, IndieBound and Target right now! And I’m not gonna be shy about this: I want this book to be a best-selling book so your pre-orders will help me achieve that goal! As a matter of fact, I will be offering some free gifts if you pre-order so come back here often for updates!

Finally, if you would like to be a member of my book launch team which means getting a FREE advance copy of Destination Wedding, email me at jacqueline@afterthealtarcall.com!

Thank you so much for reading this blog post, and I hope and pray you will be reading my first novel Destination Wedding very soon!

Any thoughts?